This one is about the mall and (again) is a long one, and yet I barely scratch the surface on so many things that I wanted to reflect on that came up watching Secret Mall Apartment. Like how fun it was to see Greta 20 years ago before we were even friends. And how relevant this song from 2000 about the Providence Place Mall by Mr. Pipes is now with its refrain “crying, wailing chapter 11”. Note that the Mr. Pipes song does not have anything to do with the Movie Secret Mall Apartment, its just a great primary source document of how artists were relating to the mall back in the day when it could still be referred to as “the new mall” (props to Dave Public for the audio file that’s embedded below below).

“So when you come to the new mall, cut your face, paint your eyes, shake your face, run amok, show me how you cut your face” Mr. Pipes

The Mall that I grew up going to was named after the poet Walt Whitman. A little bit further away was a mall where the food court was named Calder Court after sculptor Alexander Calder. One of Calder’s last commissioned pieces sat in the parking lot for a number of years, and was eventually brought inside to hang out with the Sbarros and Orange Julius and then once people realized what it might be worth, it was sold for 1.7 million dollars. The story of how the Calder and a bunch of other 1960’s high art ended up in this particular not super high end mall is actually pretty interesting and has an Andy Warhol Factory sub-plot. The point being that art and malls have a long history of entanglements. Malls are after all real estate and its time that we talk more openly and clearly about how artists and real estate markets spent a generation squabbling and hate fucking and never being transparent about which line on the balance sheet pertained to sales of art and which pertained to the sales of square footage of hardwood floors that could not be sold until churned through the gentrification machine that we have all seen so many times from so many vantage points that the horizon can only be an optical illusion. When the Mall Apartment that is the star of the recent film Secret Mall Apartment was being built, the churn and the horizon seemed situated enough in the rear view mirror, that we thought that we all knew better about everything, but still the setting sun was close enough to be burned by, especially in Providence.

As suburban malls have died and their corpses left to rot, their mythos have risen in our collective consciousness. A word started floating around to embody a longing felt for department store displays of the not so distant past: mallstalgia. On a certain level I think that everybody can feel in their bones the sundry ways that malls and the suburbias that they sprung from are a depressing cultural dead end. The arguments against them suddenly being proven irrelevant by their abject economic failures.

I moved to Providence in 1993, about a year after the very beginning of the planning for the Providence Place Mall. By 1995 I was enraptured in cultural theory and addicted to reading about modernity, post modernity, and all of the signs and symbols that were replacing lived experience as commerce and public life collided. But before that, as an alienated teenager in the suburbs, on an intuitive level I knew that the mall was a bummer. But still when god gave us a snow day, my friends and I would take the bus to Walt Whitman, play Tetris at some store that sold televisions, eat onion rings at Burger King and scope the fashions of other alienated teenagers doing the same. At this point in time there were not the Hot Topic style mall stores that catered to suburban alienation that would come in the late ‘90s. Maybe you could get like a new wave or metal tape at Sam Goody, but basically the only way that it was a place that had anything for us was that it was indoors on a snowy day and accessible without a car.

This is to say that the mall’s value to us was as public space on a transit line. But then as weirdos it didn’t take us long to realize that malls weren’t actually public space at all. All it took was handing out one flyer to another teenager about some event to be asked to leave (no leafleting) or carrying around a skateboard (because the parking lot also is private property it is illegal to skate anywhere near the mall). To me the issue of the Providence Place Mall was always about public financial subsidization through tax deals and the like, of space that has the appearance of being public, yet where basic rights are not guaranteed. I’m still sorting out my feelings about how political analysis did and/or didn’t enter directly into Secret Mall Apartment, but we’ll get there. These issues are as relevant as ever as the Providence Place Mall has just recently banned groups of more than four teenagers and enacted a curfew on teens at the mall.

A thing that people used to talk about more often was how the first ever enclosed shopping mall in America was the Arcade in Providence on Westminster Street built in 1828. Now its mostly apartments and like one pretty ok falafel place. In the aughts, before it became condos or whatever it was a weird assortment of half failing stores on two levels including one that sold work by local artisans that also hosted an artist residency in whichever storefront was currently vacant. I think that it was in the summer of 2002 when I got to do a residency in one of these store fronts. It was my first ever artist residency, which is funny because now my job and to an extent, my life sort of revolves around artists residencies.

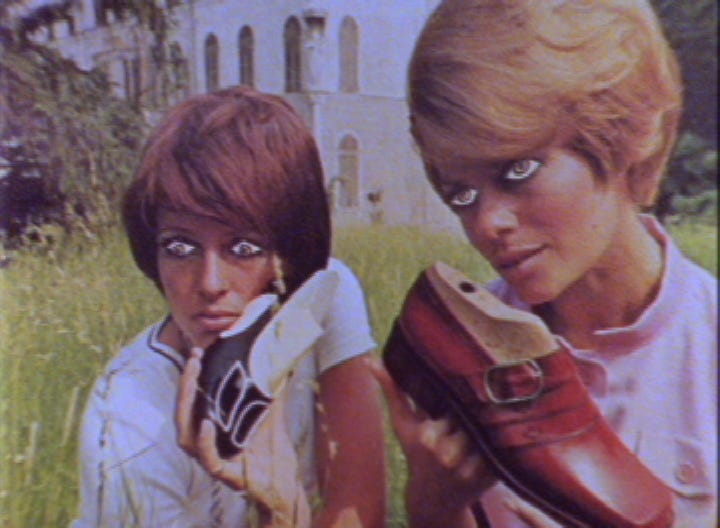

It was a weird experience. I had the space for a month and I wanted to set up a fake store and talk about commerce and sell things or talk about selling things to people hyped on buying things at the mall, but also I sort of just wanted to hide and sit in an oddly carpeted empty room with fluorescent lights and meditate. Sometimes I think of that residency as a massive failure where all I did was put clippings from Italian trade shoe magazines into three dimensional paper frames while listening to a boom box playing the news all day. Maybe that was when I got sick of the radio news. But then I remember that I made a movie that has likely screened more than all of my other movies combined. Its sort of a one line joke of a movie of the Italian shoe models rolling their eyes. You never know why or when you will make the thing that resonates. And sometimes the “popular” work that you make will feel vacant. I was also obsessed with neon colors and each afternoon I got a diet coke big gulp from the nearby downtown 7-11. The mall was slow, but still sometimes I would feel like a zoo animal and so I gradually started hanging things up on the big glass windows so that people would really have to try to peep between the stuff to see in. But then I put up this drawing that was like a trick of perception where if you look at it one way you see a woman looking in the mirror, and if you look at it another way it looks like a two legs with a hand between them doing what hands between legs do, and i guess word got around and people started coming by to look at this drawing, which was not what I wanted. Now along with existential feelings of doubt, I also had to contend with intrusive thoughts about how I might be getting in trouble for hanging up a masturbation drawing at the oldest mall in America. Eventually the mall manager did come by and peek in and I preemptively was sure that I was going to jail for indecency or something. Sorry mom.

When I think about artists who compulsively flirt with trouble, but also have an impeccable track record of getting out of it, Mike Townsend (one of the masterminds of the Mall Apartment) is the first artist who comes to mind. Probably the most meaningful conversation I’ve ever had with Mike was when I was trying to get him to contribute to a compilation of stories by local artists that I was putting together on the topic of trouble. He talked fluidly and matter of factly, with neither guilt nor apology about the relationship between trespassing and privilege, boundary pushing and safety nets. I never got him to write or make anything for that book but its still a pretty epic compilation.

At the Arcade, it turned out that the mall manager thought the drawing was funny and the trouble was in my head. But as the residency rolled on, I wasn’t happy with what I had gotten done. There was going to be an opening and I thought that I should stay there one night to work all night, because at the time another deranged idea that I’d gotten into my head was that if I didn’t stay up all night working on an exhibition, was I even working at all? If I wasn’t visited by the spirits of 3 am insights and the lonely quiet of the sleeping city, could I know anything worth sharing? If I wasn’t loopy and sleep deprived at an opening, gnarly with ketosis induced bad breath, would I even know how to socialize with the middle aged people who worked downtown who I imagined would be the audience for openings at the Arcade? So eventually I decided that I would stay overnight in my makeshift mall studio before the opening. I was pretty sure that if I left to use the bathrooms in the basement after hours that I’d set off some alarms, so as I hatched this plan I started to save the big gulp cups to pee in. There were folding tables that I worked at and when it was the time when the security guards were closing up I put a big piece of fabric on the tables and hid underneath them, my stomach teetering between feelings of thrill and nausea. One of the hardest things about being an artist is that no one tells you what you’re supposed to be doing. And value, both conceptually and materially are massively subjective.

Inside of this community becomes everything, and this is one of the most beautiful and rewarding things about being an artist. I think that I will carry with me to my death the belief that the community of Providence feral twenty something artists who I came up with was one of the most magical and rigorous cohorts of young artists that this country has ever seen. Although I also hope that every cohort of young artists everywhere feels this way. But the thing is, when something is so special and rooted in all kinds of wild ideas, and also when a good half of the things that are being done are not totally legal and are happening in places where no one is supposed to be, then things need to be secret. They need to be underground.

Just like in art there are no written rules in the underground. No one tells you what you’re supposed to do or not do. But there are some things that are pretty obvious. Like don’t talk to cops or journalists. One time in the early days of the Dirt Palace, back when the Providence Journal actually had writers who covered art events, a reporter named Bill came to a puppet show. He stood out like a sore thumb in his button down and Pippi and I were tag teaming trying to explain to him why it was really important that he didn’t write about the event in the ProJo and that like if he actually cared about art he would not jeopardize the shutting down of a space like ours by telling likely indifferent Projo readers the sundry details of the ballad of some styrofoam ball heads mounted on chopsticks. If you write about this we argued, you are going to be fucking things up for a lot of people by tipping off the Fire Department. He said that he would write what he felt moved to write. On that cue, Dan, Pippi’s boyfriend at the time moved forward and said something to the effect of, it seems like you’re threatening my girlfriend and you have now unleashed the gorilla. Dan, who had a gorilla face tattoo that covered his chest, pulled off his shirt and stood there with crazy eyes. Bill the arts writer got the fuck out of there and apparently was no longer moved to write about a puppet show being performed in a hallway that smelled like garbage in a building in Olneyville that still had boarded up windows.

That’s a long winded way of saying that when in January of 2022 when Documentary Filmmaker Jeremy Workman’s email with the subject line “interview request about Secret Mall Apartment” landed in my inbox my abreaction was to think to myself, who the fuck does this guy think he is and does he really think that I’m going to narc this shit out. Honestly I don’t even open most emails that are requests that have something to do with talking about the old days of Providence. Most of it is related to memories of someone who lived here for a year or two in the late 90’s and I have lived here for 30 odd years and while those late 90’s years were magical and special, so have been most of the other years.

What I’m getting at is that nostalgia feels like a betrayal of the present. And also a betrayal of a whole bunch of other pasts, and so I try not to go there, to that place of idealizing other times. But anyway, I finally like, actually read the body of the email from Workman and kind of had to eat shit. It was long and not generic, and I could feel it anticipating my skepticism in every sentence, but it never struck a defensive tone. The author of this email understood what he was up against and was graceful and generous at every turn. So rather than throwing it directly in the trash I let it hang out for a week or so. Then like any normal person, I googled the shit out of the sender and figured out what mutual friends we had. My friend Peter had worked with him on some freelance gigs in NY, but more importantly a friend of his had been the subject of one of Workman’s previous documentaries and Peter thought that the whole thing was really positive and cool. I tell you this to give some insight as to what kind of scrutiny and community back channel vetting this dude went through by assholes like me who are only marginally connected, but protective, probably to a fault of beloved secret histories of Providence.

The telling of stories connected to underground scenes can’t be told by just anyone. When we were younger I think that a lot of us focused on notions of “selling out”. But I hardly think about that anymore, and I’m not sure if that’s a product of aging, or if the whole economy around art has gotten so much of the air sucked out of it that you’re just cheering for anyone who can make a go of anything in a reasonably half financially sustainable way. Now my concern mostly has to do with stories getting the basics wrong and making people who choose to live in ways that don’t fit into traditional molds out to be eccentric freaks.

I’m telling you about my initial skepticism when Workman’s email arrived, not to reinforce ideas that are likely floating around that I’m a judgement asshole gatekeeper, but rather because I think that its a good segue into the core idea and approach that I ultimately think makes this film successful. And that is that it is centered around public art. By 2003 when the mall apartment is underway, Mike is already a pretty seasoned public artist and the crew of younger artists building the apartment with him are also working with him on public art projects. All art is dependent on complex ever shifting relationships between makers, viewers, meaning, context and a bunch of other interconnected nodes that I often visualize in my head as string figures or loose knit lace. Public art is unique in that if just one or two little nodes are off, people literally start toppling statues, or mobilizing for their removal before they’re even installed. Public art failures can be intense and painful. Tilted Arc, the South Bronx Bronzes. Every day Mike and the Tape Art crew are negotiating with living humans about ways of altering the lived environment of these various living humans. Often the environments are shared. The negotiation is the art. The listening. The artist showing that they understand the perspective of the viewer. The dance of navigating multiple perspectives is a daily exercise routine where the muscle mass of trust is built slowly but surely over time. The word stakeholder vibes a little corporate to me, but it's such an essential part of a public art project: assessing who might be stakeholders, and figuring out how to intersect and approach them. When public art goes well, it affects how people feel about the places where they spend time, places where civic identity is generated and shared. When it goes wrong, there are bummer lawsuits.

A legend is maybe the oldest and purest form of public art. The beliefs and values of a group of people become embedded in a shared text. To know a legend is a form of belonging, to know a special element of the story in a deeper way is the stuff that communities, cultures, cities and even countries are built on. To be a legend a work of art has to not just stir feelings in an audience, but those feelings must be civic in some way. The story of the Mall Apartment was a Providence legend for a long time. The question for Workman was: could he, using the tools and distribution mechanisms of cinema widen the circle of who felt moved by this story.

In weaving together stories of Tape Art and Mike Townsend’s work in public spaces with the story of the Secret Mall Apartment, a set of underlying ethics and corresponding aesthetics are made apparent. Workman’s approach from the jump, of paying a lot of attention to stakeholders, is something that I now interpret as an attuned alignment with Mike’s ethics and approach to public art-making. I’m not sure of how much the two of them discussed these things in plain terms, or if it was more of an intuitive sense that Workman’s sensitivity, craftsmanship and experience telling the stories of people with persistent visions was the right avenue for bringing increased visibility to the story of the mall apartment.

The story, of course, has been told in other forms. But none of the other forms possessed the potential of bringing the project full circle to durationally occupy major real estate in a mall the way that of a feature film with a theatrical release could.

The most widely circulated media about the mall apartment pre-movie was an episode of the podcast 99% Invisible called The Accidental Room. It's good, but its focus is on the weirdness of the building design that led to the existence of the mall apartment space and it speaks the language of architecture and urban planning, which is a relevant framework for this project, but not, I’d argue the most important one. It always felt like there was a place for the Mall Apartment amongst the canon of art historical works that take on relationships between real estate, architecture and capitol like the work of Gordon Mata Clark or Theaster Gates. But the film operates more in the realm of heist movie than in the art world, which is, of course, a political choice.

My favorite pre-movie secret mall appearance is in the novel Exes by Max Winter, a book that between the plot lines reads like an almanac of Rhode Island legends: the founding father’s corpse as apple tree root, clingstone, scrimshaw he’s-at-homes, Despair Island, the fountain on Benefit street, directions involving long gone businesses and of course, the mall apartment. Because Exes is a work of “fiction”, the details are mangled and skewed, and the character, Cliff Hinson, who is the lead mall dweller through who’s voice we hear the story of living at the mall, is certainly not (all) Mike Townsend. Most of the characters in this book are bizarre mash ups. I think it is a bad idea to attempt to reverse engineer the complicated character medelies that Winter has drawn up, that said a little bit of detail detangling is hard to resist. For example Cliff mentions drawing on the mall apartment’s walls the rooster that he used to own that cock-a-doodled-do’d every half hour. I can assure you that it was in fact John Dwyer who owned this mill dwelling rooster. It lived across the hall from me at 556 Atwells (the other side of Eagle Square) where the walls were 12’ 4” and the landlord had cheaped out when divvying up the former factory floors by only actually installing 3 pieces of drywall on top of each other, meaning that the top 4 inches of wall did not exist. There was so much space in the mill that most of the time this didn’t matter, but when that fucking rooster was announcing dawn over and over all day long, you could feel that 4” gap. At times Cliff’s account of the space is more intimate than what we get in the movie Secret Mall Apartment, even though it is, as far as I know, totally made up.

We moved in the secret room piecemeal, stuffing what little we needed into duffel bags and making trips a couple-two-three times a day under cover of the busiest business hours. We brought some pots and pans, a hot plate, milk crates, clothes, a stereo. There was also what was left of our old space. The building’s new owners figured it was garbage, so they hadn’t thrown it out. It took a whole lot of trips to get the caftan maze down there, and the wall’s worth of action figure torsos. My hips started to hurt from all the up and down, but that’s because we’re meant to live in trees.

When I had the residency at the Arcade I realized that bringing a bunch of stuff downtown in a car that you had to park was a pain in the ass and so a couple of times I pushed a granny cart full of materials from where I lived in Olneyville to the Arcade. The walk itself, a summer spectacle. What I remember of the night that I stayed there was that when I was awake and in the zone I felt exuberant, but then when my energy started fading and I hit exhaustion and doubt, it was painful and not very fun. When at dawn, I finally did attempt to lay down under the table to avoid the part of the day when the lights got turned on, I could only sleep in like 15 minute chunks and then my hip rebelled against pushing against the floor with no padding and I’d have to keep shifting sides like a rotisserie chicken.

While I don’t actually know what it was like to crash at the mall apartment, the movie backs up my speculation, that it fell on a spectrum ranging from exuberance to awful sleep. The material aspects of spending time in a fucked up place that’s not built for living and where you’re not supposed to be sleeping aren’t that mysterious to me. We were all doing this a lot in the 90’s. A few nights in a studio here, a night in an abandoned building there, someone had the keys to the old Woolworths. Everyone had hacks for eating food with filthy hands when there was no running water and kept a piss bucket under their desk. The curiosities that I came to the film with were about the spiritual aspects of what it was like to live like this, but nestled, not amongst the ruins of industry, but rather inside of an engine of hyper-powered consumerism. Sometimes I felt like I could glimpse answers, but most of the time the primary source documents were emotionally blurry.

The Providence Place Mall opened in 1999, the same year as the WTO protests in Seattle which are often seen as a critical moment in the anti-globalization movement. Protesters included anarchists, major unions, and far right idealogues like Pat Buchannan. Everyone knew that America’s economy was changing. As young people in the 90’s the course of our lives were marked in unique ways by extremely cheap rent in the leftover warehouses and worker housing abandoned by the steady stream of factories that had moved overseas. Politicians and economists would tell us that it was good that we were shifting from a manufacturing to a service economy, but the 90’s economy vibed more bloated and sinister than “good”. Cities were precarious with all of this empty space and the jobs that seemed to be replacing manufacturing were bullshit dead-end retail jobs at the mall. Professionally someone working in the service economy could range from a doctor to a housekeeper - which is to say that there wasn't much coherence or solidarity in this so-called sector. It didn’t add up and the news was all about Enron and other stories of corporate America screwing over workers.

In this dramatic shift of economies, I think that one thing that leaders neglected to take into consideration was that manufacturing in the United States was kind of a legend. As a nation, it was how we grew our wealth, how we had jobs to welcome immigrants into the country, how we won the good war, and how we took steps towards gender equality (with Rosie and all that). There is inherently a satisfaction in making things, and this satisfaction coupled with propaganda about the freedoms won through the things made by American Industry and the reality of hard-won union living wages in the manufacturing sector created an imagination of manufacturing labor that meant more to American’s civic sense of self and its place in the world than the sum of mere data points. NAFTA went into effect in 1994 and dealt the death blows to much of the lingering manufacturing in the US. This brought together what in hindsight was a very weird coalition in 1999 in Seattle.

Providence was far from Seattle, but the loss of industry was living with us day in and day out. It was a huge part of our lived reality. While we young people were attempting to construct utopias in the ruins with walls literally built out of garbage and other excesses of capital, leaders were throwing garbage like shopping areas and strip malls at the walls and seeing what stuck. We were in our 20’s and maybe some of the things that we were building were too dangerous or beautiful to last for long like Fort Thunder, but all of the shit that they were suggesting was rotten with greed, exploitation, environmental harm and/or just simply idiotic. The proof is in the pudding of the failure of the first anchor tenant at Eagle Square and the defaults on payments of the Providence Place Mall. There is an irony that there are certain alignments between today’s MAGA economic policy and the anti-globalization ideas anarchists were getting in the streets of Seattle for in 1999. The main difference being that anarchists then were talking about impacts on labor and environmental standards and also that in ‘99 the infrastructure of American Industry was dusty, but not entirely dismantled as it is today. But still it ought be kept in mind that politics and economic policy today are not out of the grasp of the myths and legends of American manufacturing.

The Providence Place Mall was a weird bad idea, but as Leonard Cohen has told us, there are cracks in everything. The crew building the Mall Apartment found the crack and held strong in it for four years, but maybe even more importantly held onto the story for twenty years, and now it emerges as a legend that answers some questions about cities and industry at a time when we could use new legends and ideas more than ever.

With the mall in receivership, new thoughts about paths forward for it are surfacing including ones that have (drumroll) apartments in the mix.

I'm so grateful to have this in my inbox after seeing the Hudson, NY, premiere of Secret Mall Apartment last week (shout out to TSL, a space that everyone should pin if they come to town). Seeing you pop in at the end was, of course, thrilling. I have so many favorite parts of this reflection piece (thank you for that Mr. Pipes anthem), but having that shared understanding of as you said so perfectly, "The material aspects of spending time in a fucked up place that’s not built for living and where you’re not supposed to be sleeping aren’t that mysterious to me. We were all doing this a lot in the 90’s," made me reflect on all the wildness that was going down in the nooks and crannies around the country. All to say, I always struggle with not falling face first into nostalgia and don't miss piss buckets. Thanks for another banger Xander <3

Amazing writing Xander. Somehow this wove together things that are both deeply personal and globably pertinent. Really gave me a lot to think about and reflect on, thanks for sharing this!