A PRESIDENT'S DAUGHTER IN PROVIDENCE and the case of the mysteriously disappearing student cooperatives

I started working on this piece before the inauguration and the ensuing shitstorm of executive orders, which are so clearly an onramp to fascism that it is hard to psychically think outside of them. But I stand by some of the questions raised in this (very) long form essay and offer it as distraction, or maybe something more if you are the kind of person who likes to think about building longevity for projects with anarchist tendencies that no one is sure of how, or if, should move into middle-age or beyond.

This installment of Wild Goose Chase is a little bit different. Its jumping off point is a location in Rhode Island, but not as in a town or street as I’ve written about in the past, but rather as in a collection of specific houses on the East Side of Providence. These houses have been the sites of endless stories, wild parties, the butt of jokes, an impossible dream of cooperation and collective ownership, they have provoked neighbors to keep code enforcement on speed dial, single handedly brought down property values on an uptight and hyper-gentrified street and now they are ostensibly gone in their current incarnation? Without fanfare, or much information - no official posts about their demise on the internet. Their death seems to be a first rate mystery deserving of an actual investigative journalist, of which I am not.

But I have some stories and some questions and I daydream that maybe the combination of these things could stir the interest of someone with more skills and/or resources than I have for getting to the bottom of something that smells, if not rotten, then at least like overripe co-op compost. If you are not familiar with co-op compost, let me tell you that it is powerful stuff. While living at Milhous (75 Charlesfield St) in the mid 90’s hungry rats lurking in the un-enclosed compost dug deep enough to have hit buried power lines and doing as rats do, ate them. Thus causing a power outage affecting most of Charsfield Street, including the police substation. The police had no patience for this type of antics and were furious. But who’s fault is it when the rats don’t check in with dig-safe? The police said wrong question, rats don’t make phone calls. This is why it's not worth trying to talk reason with cops. No imagination. Anyway, I say that we are talking about houses plural, but the star of this particular show is Watermyn Co-Op. Because I am a sucker for history, timelines and dot-connection please bear with the Jimmy Carter sub-plot. I’ll admit that the subplot is here to also raise the red-flag of historical relevance. Does it mean nothing that the child of the one time President famously lived in this house while failing out of school because she was protesting apartheid too fervently to focus on things like actually going to classes? Is this not a piece of Providence history worth preserving?

Without complicating lines of inquiry too much, I want to add that part of my interest in digging into this story now has to do with the efforts to organize at Atlantic Mills. The student co-ops were born out of organizing during a time of upheaval and then had a run of over 50 years, which is pretty impressive. And yet they managed to disappear without so much as a public whimper. How does this happen? What cautionary tales are to be drawn from this turn of events? How do we sustain things that our movements have struggled for in the past, and not take for granted the fruits of the radical labor of our elders that may be politically imperfect through the lenses of the present. In short, how do we maintain collective leftist projects on both material and spiritual planes? How to discern what’s worth keeping and not accidentally let the baby get thrown out with the passive solar heated bathwater?

*****************************

As a kid living in the DC suburbs in the late 70’s, we grew peanuts in the backyard in homage to the then president. I would dig in the dirt and pull up the peanuts, put them into my red wagon and walk around trying to offer them to people going to the movies. The problem was that there wasn’t anyone going to the movies in my backyard, except for me and when I talked about going to the movies, what was really going on was that I was sitting on a cinderblock under a darkish pine tree. I would sit under there for hours just spacing out and staring off into the distance, pretending to be watching movies, but really just enjoying the quiet and sometimes elaborate visions projecting from my five year old mind's eye. If you have ever wondered what the warning signs are that a child might have experimental film-maker tendencies, I offer this anecdote as cautionary tale.

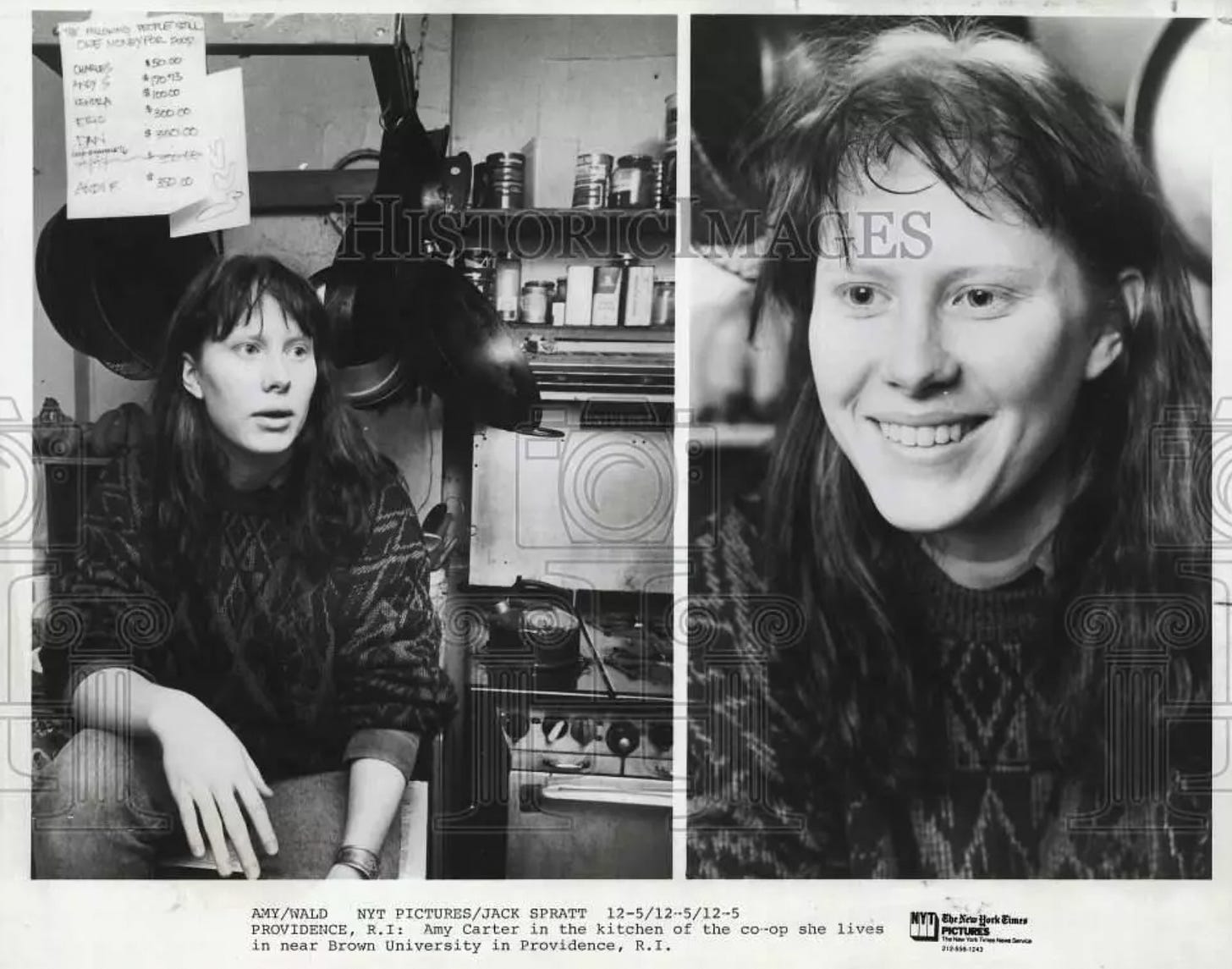

At this current moment in political history it is hard to imagine thinking about American Presidents and being anything other than exhausted, fearful, and freaked out but I hold that if there was an administration to come into consciousness during, the Carter Presidency wasn’t too bad. How far we seem from a time when a peanut farmer could hold such an office, when the child of the President would go to public High School, when a politician would tell the country going through an energy crisis to turn down the thermostat and wear an extra sweater.

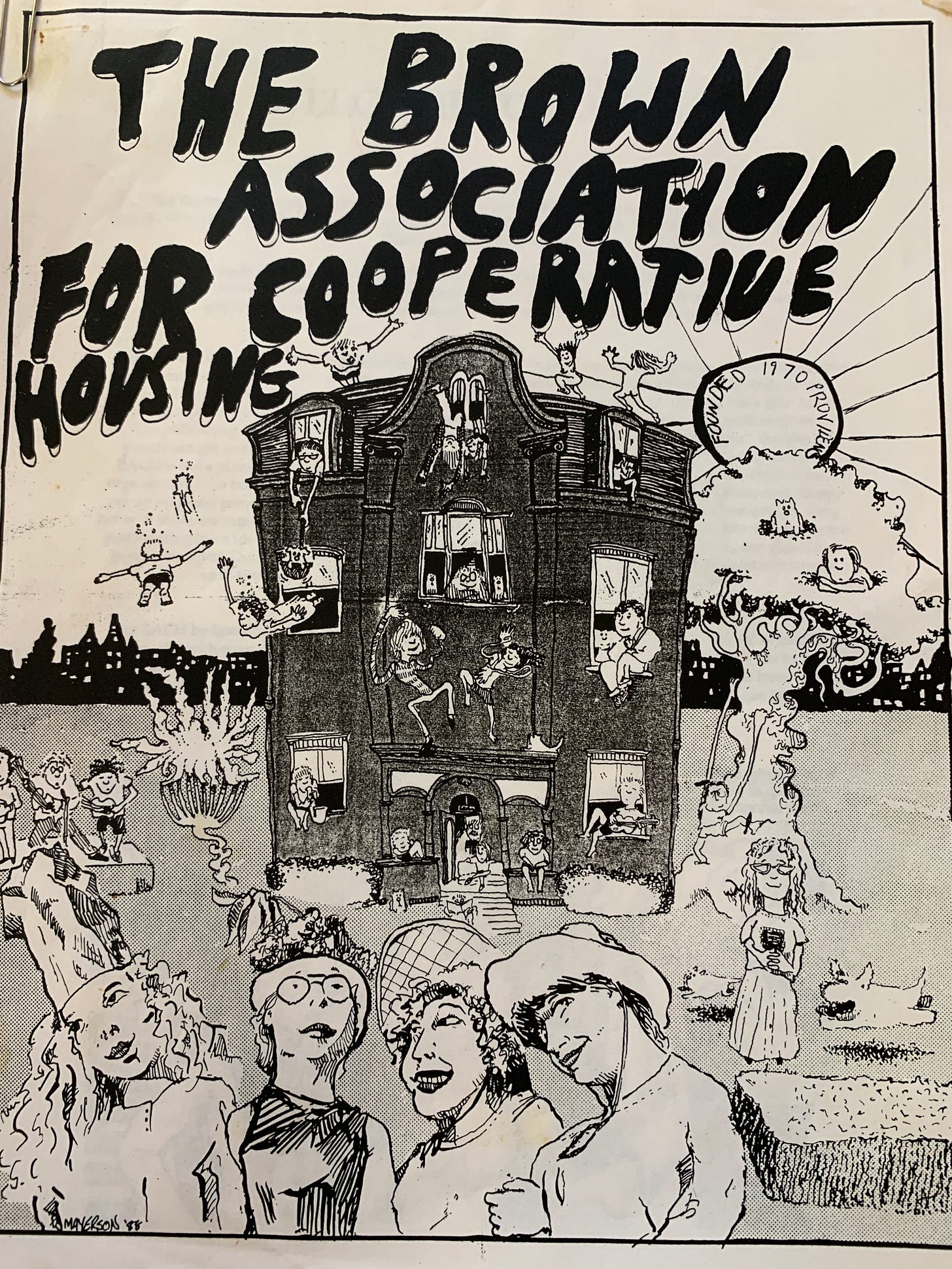

In reading over all of the stories about Carter’s legacy over the last month, I was reminded that his daughter went to Brown for a few years and lived in Providence. I had known this because it was part of the lore of the Brown Association for Cooperative Housing (BACH), a student run housing initiative started in 1970.

When I was a freshman at Brown in the spring of 1994, my friend Eliot & I threw our names into the hat for the housing lottery of these said Co-operatives and through luck of the draw managed to get into a room in Milhous. This was a big win for me at the time as I wasn’t doing great that freshman year. I mean grade wise I was doing fine, but I felt alienated from my classmates who seemed to have all gone to prep schools where they had become experts on the Carolingian Empire, catapults and numerous plagues.

Eliot and I were similar in various ways and were fast friends. Both of us were visible characters on campus whose idea of dressing down for breakfast at the cafeteria likely still involved eyeliner and a fur coat. But despite our flair for fashion, we were both pretty low drama and goofy. Our friendship was not at all romantic, and it had never occurred to us that there might be anything scandalous about attempting to live together as people of different genders. The Co-Ops were cheap: $800 a semester & $400 for the summer rounding it to about $170/month, which even in the mid-90’s was pretty good for Providence. Living there required being part of the vegetarian food co-op too, which was another $400/semester, but this meant that all of your food was paid for. Residents and other non-resident “food-co-opers” cooked dinner for 25 in a team of 3 about once a week, usually from a recipe from one of the many Moosewood cookbooks, which were the gold standard for vegetarian cooking at the time. At risk of sounding extremist, I have probably endured every recipe from The Enchanted Broccoli Forest at least once. I honestly don’t remember any co-op meals being inedible, but we got fresh bread delivered 3 times a week from The Daily Bread, which had a bakery on Wickenden St before the main operations were moved to Broadway in the building that now houses the spa with a logo that looks like a butt-plug. Point being, it was pretty easy to make yourself a sandwich if what was being served was god-awful.

Anyway the co-ops were cheap by design. The students who founded them were critical of the expanding reach of Brown University into the Fox Point neighborhood and the tendency of the growing student body to price out Portuguese and Cape Verdean families who had started settling in this neighborhood in the 1870s. The idea was that if there were more affordable housing options closer to Brown’s campus, this would curb the tide of displacement. In my research I found instances of BACH’s messaging that asserted that BACH was the first not-for-profit organization with an explicitly anti-gentrification mission. And while displacement concerns are clearly articulated in the original by-laws and articles of incorporation, I have no idea of how to fact check this claim. However, given that the term “gentrification” was not coined until 1964, it doesn’t seem impossible that the organization was the first to use the term in its application for not-for-profit status with the IRS in 1970.

My parents did not like the Co-Ops and thought them to be filthy drug dens, but they loved Eliot and I think were just glad that I had a friend who seemed both fun and down to earth. It probably didn’t hurt that he was a computer science major. As previously mentioned, Eliot and I both had impeccable taste, fantastic wardrobes and so it seemed obvious that the decor of our room would also be top notch.

Another perk of the co-ops was that you could do whatever you wanted with your room. We planned to paint the walls plum with avocado trim. I returned to Providence early for the fall semester to do the painting, which I was told would be fine by someone who answered the phone when I called Milhous the week before, only to find that when I got there no one knew who was in charge or where any keys were. Moving me into this scenario might have been part of what freaked my parents out. I assured them that everything would be fine. They drove me to the paint store, returned me to the big porch and bid me adieu. Then for the rest of the week, too shy to ask again about the keys, I climbed up the fire escape to get into my room. I kind of liked climbing, the only hitch was that this particular Co-Op was right next to the police substation, and could I essentially break into the building for a full week without rustling the ire of any cops? Yes, the answer was yes.

Pretty early into the semester, we got a call on our answering machine from a journalist doing a piece for the alumni magazine about students who lived in places with interesting decor. She said that she had gotten tips from multiple sources that our room was very cool, would we be willing to talk to her? Sure we said. I think that we chatted a little, but it turned out that it was mostly a photo shoot. I wore platform Chuck Taylors and a favorite thrift store dress. The article ran. My parents loved it and were starting to change their tune on the whole co-op situation, and then the response letters started to flood in. People who had graduated in the 1940’s who were scandalized that a boy and girl were living together wrote scathing hate-mail. One called us “Moral degenerates and fornacators”. A friend astutely observed, “neither of you have gotten laid all semester and now you're the poster children for sex on campus, you have to admit that it's pretty good prank”. At dinner one of the upperclassmen from the co-ops who was on the board said something to the effect of, “I don’t think that the co-ops have been in the middle of such a media controversy since the former President’s daughter was photographed sitting on buckets of tofu at Watermyn Co-Op.” And that was how I learned that Amy Carter had lived at Watermyn a little less than a decade earlier. According to my math it was likely the Fall of 1986 when Amy was a co-op member.

When I moved in, in 1994 the co-op network consisted of 3 houses: Milhous & Carberry that were rented from the University through a deal that had been brokered after the university had acquired them and 24 other buildings on a total of ten acres from Bryant College in 1969, and Watermyn, which had been bought by the student-run organization in 1971 (Watermyn, along with Milhous & Carberry had also been part of Bryant but it is unclear if the parcel was bought from Brown, or directly from Bryant College).

The late 1960’s/early 1970’s were tumultuous times on campuses everywhere and at Brown the curriculum was being radically redesigned by students for students. This approach, which for many years was called “The New Curriculum” is now simply referred to as the “The Open Curriculum”. The New Curriculum was based on a report co-authored by Ira Magaziner, whose son Seth currently represents RI in the US House of Representatives. The Co-Op experiment was part of the movement for students to have more agency and ownership over the design of their educational experience.

The sophomore year that I had spent as part of the Co-ops had been a pretty big turn-around for me. I felt like I had found my people and was ready to dig in deeper. I became the housing coordinator and thus a part of the Co-op board. Board members did administrative work, rather than say toilet cleaning or stair sweeping, though truth be told, cleaning type chores were probably blown off more often than they were actually done. The year that I joined the board was when things were getting hot and heavy with the purchase of a 4th house that at first was called Gnu-House, both because it was “new” and as a nod to the free operating system Gnu/Linux (the house was across from the Computer Science Department and at first attracted mostly CS majors.) The basic run down from 1995 was Milhous = punks, Carberry = hippies, Watermyn = lesbians, Gnuhouse = CS majors. This changed slightly year by year as the lineups in the houses shifted. At some point a bunch of residents at Gnuhaus drank too much vodka, received an out of body visitation from cosmic reindeer and were instructed by them to rename the house Finlandia. Shortly after Finlandia came on-line the University sent notice that it was terminating the leases on Milhous and Carberry. This was a huge crisis moment for a solely student run organization that was suddenly going up against a behemoth university that to a degree banked on the fact that every 4 years there would be full turnover within the student body and thus institutional memory of student-led organizations could be very short.

Of the things that I learned from in college that are relevant to my life and career today, all of them pale in comparison to the learning that came from being part of the student co-ops. I witnessed the closing of a real-estate deal being totally managed by nerdy 21 year olds, lived with kids who had grown up in Providence and gained perspective on local arts, politics, and came to know the cast of characters running the vibrant arts underground at the time. As housing coordinator I administered the housing lottery, assigned rooms (and sometimes roommates), shook people down for rent when they got behind on paying, practiced consensus decision making, was part of conflict resolution being learned in real time, had my first encounters with the Providence Department of Inspections and Standards (at the time under the leadership of a guy name Ramzi Loqa), figured out how to fix things that broke, learned about big picture concepts around cooperation, housing, not-for-profit ownership of property and with a team of about a dozen other students, organized and organized and organized our fucking brains out until we were all burnt out or dropped out or in Butler (the psych hospital) or looking longingly to live somewhere that didn’t involve daily battle with a billion dollar powerhouse institution who was always going to win from the start.

Ok that’s just the boring list. I also negotiated with residents at Finlandia who had 49 pot plants growing in a closet lined with aluminum foil, who refused to move them before a walk through with city building inspectors who they considered to be “the man”. This couple, a girl who went to Brown and her hippie boyfriend, refused to talk with us clothed. To be clear, we could wear clothing, but they insisted on being naked for the occasion of meeting with us. They also claimed to have guns and really wanted to pull them on the building inspector, rather than say, my idea, which was to move the plants to the grow closet at Milhous for the night. Ramzi Loqa was hard to deal with, but not deserving of having guns pulled on him by hippies. The Milhous closet, which was one block away, had fans and lights and their plants would be fine there for one night only. It took almost two hours of stupid conversation and being awkward about where to put my eyes before they finally agreed to box the plants up and move them in the back of my truck. What else, we put on shows in our living room that included the likes of Elliot Smith, Jason Molina, Palace and sundry local bands. I baked a lot of bread while reading a lot of Foucault. When Guy Debord died my housemate wheatpasted flyers up all over the city with the quote “Where there was fire, we carried gasoline” it was like that. Lust for life, the white hot heat of community as imagined by 1970’s vegetarian college students, interspersed with 90’s youth cultures, radicalism, a city moving through a uniquely strange time of corruption and lies and sometimes we had fucked up plumbing.

At some point as the eviction crisis loomed we started to look for help from a national organization called NASCO which stood for North American Students of Cooperation. I wasn’t on the front lines of the NASCO mission, as I was pigeonholed as someone who should be on the propaganda committee. This group had decided that we should stage a puppet show to rally our proverbial troops. I made marionettes that were way too big that puppeteers manipulated while standing on top of tables. The person doing the majority of the script writing was a serious student of experimental literature, heavily influenced by Oulipo, and so the bulk of the lines were both rhyming, and contained no instances of the letter “a” (it is also possible that his keyboard was just broken). I think the puppet show was successful on the level that outsiders came and understood better what we were up against, and we all became more invested as we brought creativity to our bullshit situation. It was decided that we should go as a group to the NASCO AGM, or Annual General Meeting. We drove there in a van reading aloud to each other from canonical texts about utopias and intentional communities. The conference was eye-opening. Many of the University Student Cooperatives had non-student paid staff, NASCO had non-student paid staff. No wonder we were so rag-tag and burnt out, but also many of these organizations were WAY bigger than we were. BACH became an official NASCO organization and got some guidance from the organization through the rough transition from running 4 co-op houses to only two.

After 2 years of living in the co-ops (one of which I was on the board) I agreed to do another semester, but I knew that I was winding down. I was burnt out on every level and also really wanted to take a semester off of school to just live and work in Providence. I had slowly been falling in love with the city, but knew that I had to be in Providence in a non-institutional way to be able to see the city from its best angles. So I got a job working on Thayer Street, settled into a new rhythm and counted how many classes I still needed to take to be done with this institution that I was growing increasingly disillusioned with as it flexed its muscle power to put the squeeze on the student co-ops. I figured that the best use of my remaining time would be to recruit new energy for the board, support rising leadership, and be clear about my timeline for stepping out. The folks who took up leadership in this time were truly geniuses. Add to the list of things that I learned from the co-ops: recruit people who are smarter than you to work with and it will make your work life better, and you might actually be able to leave out the back door when the time to transition comes.

The University took back the Milhous and Carberry buildings and then proceeded to mothball them for at least 10 years (1998-2008). My blood would boil every time I went to Louis diner (across the street from Milhous) and would see the houses just sitting there vacant. I was angry because A) the two houses could have supplied affordable housing for 500 students during that time span and B) the reason Brown University could afford to just hold property like that was because they weren’t paying property taxes on it (in 2008 Brown was making Pilot payments of only about 1.5M a year). It was bad enough that Brown was buying up real-estate left and right and not paying any taxes, but to hold onto real-estate and just sit on it, fuck that. In much of Europe this kind of housing hoarding/wasting wasn’t just looked down upon, but was actually grounds for losing your real estate (it was legal to squat in the Netherlands until 2010, and the UK until 2012).

According to the City of Providence recorder of deeds, in 2017 ownership of 166 Waterman (Watermyn Co-op) and 116 Waterman (Finlandia Co-op) changed from being owned by The Brown Association for Cooperative Housing to being NASCO owned. I’ve been trying to learn more about this transition and why it happened. This also seems to be when the organization name changes from BACH to PEACH (Providence East-Side Association of Cooperative Housing). I went to visit the BACH/PEACH archives that are now housed in Special Collections at Providence Public Library last week and couldn’t find much in the way of answers as to what happened in 2017 that prompted this change in ownership.

I did find some incredible old photos though.

And this is probably as good a time as any to mention some artists of note who lived in the cooperative houses. Barnaby Evans, the founder of Waterfire and Nina Katchadourian, who’s “Lavatory Self-Portraits in the Flemish Style” charmed the art-world and internet in equal measure both lived in Carberry (though not at the same time). I found cute photos of visual artist Edie Fake and writer Joanna Ruocco in the Watermyn archives, though I am not sure that either of them lived there, but songwriter Erin McKeown for sure did. There are likely many others as well, I’m not going deep on this part of the research/storytelling.

Fast forward to the beginning of the end. A couple of years ago (mid-pandemic) it was rumored that Finlandia was being traded with landlord Walter Bronhard. For Finlandia, this local real estate titan would give the co-ops two beautiful houses that would become co-ops in the future, because Bronhard wanted to build a new multi-story building where Finlandia had been. If the name Walter Bronhard sounds familiar it could be because you rented from him at some point, as he was a pretty big Providence landlord (I say was, because during the pandemic so much Providence real estate got bought up by big national investment companies, that I don’t think we really have a grasp on what the size of a “big” landlord in Providence even is anymore). But also if the name Walter Bronhard sounds familiar it could be because you went to noise shows in Olneyville in the early 2000’s. One of the best moments in Providence noise aesthetics was naming projects or spaces after dumb local stuff that might cause confusion, such as naming a band after a shitty landlord or a DIY space The Providence Civic Center, after the actual Civic Center had gotten a name change to the Dunkin Donuts Center. The name “Civic Center” was, after all, now up for grabs. At around this time a member of the precocious high-school break-out band called Japanese Karaoke Afterlife Experiment started performing as Walter Bronhard. I could not find any digitized recording of just Walter Bronhard, but some great collaborations with Dylan Going and Dave Public as Bronhard/Going/Public are here.

In mid August 2023 my friend Jenn (who was the BACH coordinator a couple of years after I left) and I texted each other photos of Finlandia as it was being demolished, and then shared rumors that we had heard about the future new co-op houses. But by August 2024 I started to hear rumblings that the new co-ops were being liquidated, that actually Watermyn was being evicted and everything was going to be sold.

I got in touch with Jenn again and my friend Shayna, another powerhouse BACH leader of the late 90’s and in August wrote the following letter to NASCO:

Dear Staff and Board of NASCO & NASCO Properties,

We are writing to you as alumni of the entity formerly known as the Brown Association for Co-operative Housing that currently operates as PEACH. We were involved in the late 90’s when Finlandia was first purchased and placed into operations and when the university was evicting 2 leased houses (Milhouse and Carberry). The eviction crisis led us to look for support and technical assistance from NASCO. We have fond memories of attending the AGM in Ann Arbor in 1996. We have been following the sale of Finlandia and acquisition of two additional properties. With this history in mind, we were confused by news that NASCO was now evicting Watermyn coop and has plans to sell off assets in Providence. We are looking for clear information about this situation, as currently nothing public exists on your website or social media. We would also like information regarding what NASCO is doing to help relocate current PEACH residents into alternative suitable housing.

If NASCO does not have the capacity to support PEACH, we believe that the assets should be transferred to a Providence based affordable housing organization that has the capacity to keep resources for affordable housing in Rhode Island. We have been told that financial issues are part of what is motivating this decision. This is both unfortunate, and not apparent from a review of both NASCO and NASCO Properties 990’s that are publicly available. The asset to debt ratio of NASCO properties for the fiscal year ending in 2023 looks healthy.

Regardless of your organization’s financial health, we believe that a resolution of the current situation that dissolves the PEACH houses, sells the assets and takes the capital out of the local ecosystem is extractive. It is also a breach of trust invested in your organization by previous generations who invested their resources into the development of these facilities intended to be long term local affordable housing for students and residents in Providence interested in cooperative housing.

It is our understanding that residents are expected to be out of the houses soon. We hope that your organization can respond to this query before residents are expected to relocate.

Xander Marro, Jenn Steinfeld, Shayna Cohen

*************

We received no response to this correspondence, and so I did the very gen-x thing of picking up the phone and cold calling a number on the NASCO website. The person who I spoke to was aware of the email that we had sent, though seemed surprised that we had not been responded to, but quickly told me that it wasn’t actually her work hours and that she couldn’t really talk now (though I called during hours that were designated as her “office hours” on the NASCO website). There is still no information on the NASCO website or on any of their social media. The Wikipedia entry on NASCO still claims that PEACH is a member, though through the City’s deed portal I found that the 166 Waterman (Watermyn co-op) property had been sold in December 2024 for $800,000. As a not-for-profit administrator, it boggles my mind that NASCO did not have at very minimum some bland stock communication to quickly respond to our letter with - like are you so low-key that you don’t even think to get out ahead on damage control when doing something potentially controversial like liquidating the assets of a member co-op?

My estimate is that the combined value of the assets that NASCO is selling off in Providence is in the range of 4 million dollars (166 Waterman: 800k, 169 Waterman:1.6M, 400 Angel St: 1.4M) From looking at 990’s (publicly accessible not-for-profit tax filings) it seems like the value of their whole portfolio is only about 6 million dollars. This raises A LOT of questions, both practical and ethical. The main practical question is, how much capital had NASCO properties actually sunk into Providence? The ethical question is, if a mission based national financial organization puts x amount of dollars into an organization in Providence, those assets appreciate, and they then sell them for 100 times what they initially invested is this usury? Is it ok if they’re planning on using the funds to do “mission” work in other places? It is entirely likely that there are ways in which PEACH was not holding up various parts of basic deals. But did the punishment (complete divestment & the taking away of all resources) fit the crimes?

While I obviously have a fondness for these co-ops, don’t like seeing affordable housing in Providence sold out and am not an entirely neutral party, I’m not wound up in the heat of the situation. Through various day-jobs and community work in housing, I’ve seen a lot over the years. Including dynamics where the froth of the big money of real-estate and the values based idealism of mission based leftist organizations collide in volatile ways. From this vantage point there are a couple of obvious issues that come forth in the NASCO/PEACH situation. The most glaringly problematic thing going on is that NASCO as a not-for-profit organization is in the business of educating, providing technical assistance and helping their member organizations to succeed. While its related business entity NASCO Properties, as a real estate development entity has a lot to gain if an equity rich affiliate fails. This conflict of interest is shitty, but it's probably not actually illegal.

My sense is that PEACH had zero in the way of legal standing once the deeds went into the NASCO name. But why would PEACH have given over so much equity? Tax records indicate (and an informal conversation with a former member backs up) that in 2016 (then BACH) got behind on property taxes and Watermyn was going to go up for tax auction if the tax bill wasn’t paid. NASCO came to the rescue with the money needed to pay the taxes - the buildings at this time were worth at least a million dollars together, but NASCO ended up with both deeds in its name for 50k. So there was a crisis, but also absolute trust that aligning with this national organization would help with expertise and the management issues that had gotten the co-ops into this place.

Interview with the chickens living in the Watermyn backyard (the co-op coop)

Wild Goose Chase (WGC): Hi, its nice to be talking with you bird to bird, can you introduce yourselves and tell our readers what kind of ducks you are?

Hennifer: Thanks so much for talking with us. First of all we’re actually chickens, Rhode Island Reds to be specific. Next,everyone is pretty much dead except for me, but they’ve agreed to join this interview as ghosts, so this is really a very special conversation. Coming to us from the other side are Dots and Valerie who were taken out by hawks, Biscuit who got kicked like a soccer ball by a random sociopath walking by our coop, Doorknob was was bullied by Esther who pecked at her butt and then it got necrotized, and then there is Esther who got hers from a cat.

WGC: wow, that’s a lot of history right there, you’ve taken us through the story of the downfall of the coop so directly, I wonder if you might be able to take us through the story of the downfall of the co-op with the same kind of candor?

Dots: Yeah, chickens get a bad rep for fucking around, endlessly crossing the road or what have you, but I can assure you, we can give it strait like the best of them.

WGC: When would you say that the beginning of the end was? Was COVID really hard? Was there fowl play?

Biscuit: I’m going to mostly ignore your fowl play question, we’re always playing, and always dead serious. Anyway things started to decline well before COVID, maybe starting around 2016, there was a crew who lived at the house who just didn’t pay rent. 3-5 people coming and going over 3-5 years each who just didn’t pay at all. We were here doing our part popping out eggs every fucking day, but you know humans can really get weird when it comes to distributing labor and resources and the like. Everyone liked the people not paying rent. I don’t know what was really going on

WGC: huh, that’s interesting so even though their actions had the potential to tank the whole co-op project no one got mad at them or asked them to leave?

Valerie: Exactly. I don’t know what the humans were thinking, but Brown University is a weird place where some young people’s families have so much money, and the people not paying rent didn’t have money, and it probably just made sense that someone with more money would figure it out or take care of it eventually.

Biscuit: it is not confusing to me how the other people cohabitating with people not paying rent who they liked, a student housing coordinator per-se, might not willingly jump into the role of enforcer and take action to evict people who were otherwise in good standing, who were otherwise friends. Once NASCO was in the loop it was assumed that they would help manage these kinds of issues. No one wanted to be the man, no one was getting paid to be the man, nothing made it worth it to be the man, and when you are taking housing away from someone who needs it, it is hard to not be seen, or to see oneself as the man.

Doorknob: Yeah, just like no one in the coop wanted to be the enforcer when Ester was pecking at my butt

Esther: I see now that I should have taken more lessons from the people living in the co-op about hierarchy, but I felt deeply embedded ancestral urges to establish myself in the pecking order. I’m so sorry for how my actions hurt you, Doorknob.

Doorknob: Apology accepted Esther even though you basically killed me.

Hennifer: The Co-ops were an interesting and practical learning experiment in non-hierarchy and collaboration, but they were born of an era before the nuances of “equitable” and “equal” were hashed out in hundreds of memes on the internet. My guess is that cultural growth on some of these fronts outpaced structural growth inside of the organization which left interpersonal relationships in a limbo leading to residents who didn’t fully respect or buy into the project. Its a lot of work to keep up with the times. And people need transparency not just about finances, but also about how the finances tie into core values to put work into a project like this.

WGC: That’s a really astute comment Hennifer. Rifts between the idealism/openness of intentional communities and problems with individuals who put their needs front and center without worry for the impact on the group are as old as intentional communities themselves.

Doorknob: Yeah, It can at times feel like intentional communities who are forced out of existence by an external force are lucky in comparison to ones pushed over the brink by the heartbreak of falling apart to forces on the inside. In the end it seems hard to say exactly which camp BACH/PEACH fell into. There was a ton of “grey” in the situation with the group who didn’t pay rent, and in general they were beloved and considered positive co-op participants outside of the rent situation. But a couple of years later there was a ÷person who was straight up embezzling, which, even in Rhode Island, is not so much a moral/legal grey area.

WGC: Wow, ok Doorknob, you just kind of dropped a bomb, embezzling eh?

Doorknob: Well you told us to be direct.

WGC: I appreciate you, Doorknob. Wrap up question, how are you all feeling about 2025?

Hennifer: Both totally fucked and powerful. Bird Flu is raging and we’re all going to die, but we’ve got the economy by the balls or huevos as they say in Mexico.

WGC: Aren’t most of you already dead?

Dots: Well we’re going to double die. Eggs are going to cost $8 a dozen and everyone who processes poultry is going to be deported, so there’s a good chance that chickens are going to be talked about a lot this year, which is fine. The more time people are talking about chickens, the less they can be eating chicken just based on a basic can’t talk and chew at the same time logic.

******************

I’ve been struggling to write a conclusion that neatly ties together the threads of this story. If you’ve been able to get to the end of this piece I feel that I owe you something useful for your patience and willingness to roll with wildly different components and approaches to telling this tale. Mostly what I’m feeling however is that there’s suddenly a lot of work to do right now. Every few hours for the past few days a text message has rolled in from a different friend who has had a realization about a way that their life is already being fucked with and being made harder by this administration: a passport issue, a green card issue, medicaid insecurity. I’m sad to see the Providence Co-op’s go, particularly Watermyn with all of its history. I wish that NASCO had handled the situation differently, but in the big picture, it's undeniable that what NASCO does, is decent, vital, probably often thankless work. I hope that NASCO takes very seriously all of the love, labor, wildness and care that went into building up the assets that they cashed out of Providence, and uses them in a thoughtful strategic manner that benefits a lot of people digging into cooperative experiments in other places, and that maybe they still consider investing some of it back into Providence.

This was the Saturday night read I didn't even know I needed. Double dead indeed.

Tremendous work as always.